Elbow pain on the outside of the elbow is most common in individuals’ aged 30-50 y.o. and effects 1-3% of the general population (Shiri et al. 2006). Risk factors for this condition include blue collar workers utilizing repetitive gripping and manipulation in the work place, smokers, and tennis athletes. This condition has previously been described as tennis elbow or tendonitis. The first term is a non specific umbrella term and the second has been proven to be incorrect based on our current understanding of the pathophysiology behind this condition. Tissue sampling of the wrist and finger tendons running along the outside of the tendon has failed to show any inflammatory cells making the term lateral epicondylosis, epicondylalgia, or lateral elbow tendinopathy more appropriate.

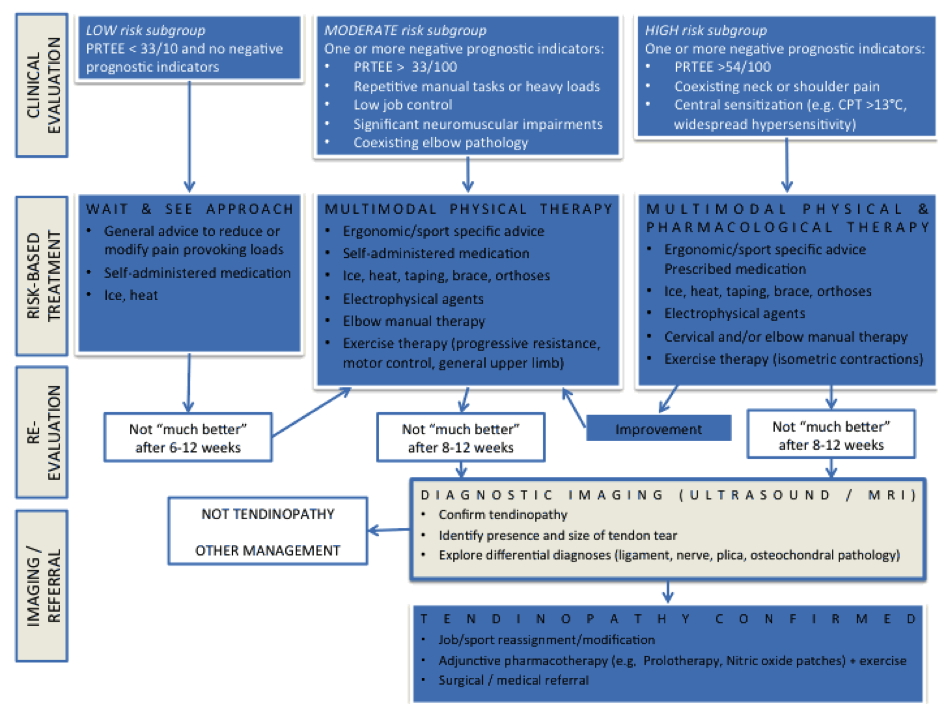

These terms suggest a more degenerative condition consistent with increased cellular and collagen formation (Cook et al. 2009). Our previous blog post detailed the ineffectiveness of anti-inflammatory treatments, including NSAIDs and corticosteroid injections, for the long term management of lateral elbow pain. In fact, corticosteroid and platelet rich plasma (PRP) injections have been shown to have poor long-term outcomes and the highest rates of recurrence among conservative treatments (Coombes et al. 2013). Recent evidence advocates for early diagnosis and management based on an individual’s unique presentation (Coombes et al. 2015). Differences in the clinical presentation of this condition are normal and our examination and treatment must be based on the patient’s presentation.

Clinical examination involving pain at a patient’s lateral elbow, and pain with gripping or finger and wrist extension is consistent with lateral elbow pain. Caution is advised to rule out competing diagnoses including referral from the neck, nerve entrapment, ligament tears, and elbow instability. Clinicians should examine surrounding areas of the body to determine their impact on pain processing and/or

Patients with higher levels of baseline pain and disability require early interventions due to the poor long-term prognosis associated with this presentation (Smidt et al. 2006). This patient population may also present with greater symptoms at rest including night pain interfering with sleep patterns. Another factor often associated in patients with lateral elbow pain includes concomitant musculoskeletal complaints in the neck and shoulder. A treatment plan aimed at treating impairments in the upper quarter, in addition to the elbow, may accelerate recovery and reduce future recurrence (Cleland et al. 2005).

Conservative treatment remains a hallmark of lateral elbow tendinopathy. The vast majorities of patients treated conservatively with either a wait and see approach or with Physical Therapy demonstrate improvements in pain and function at one year (Bisset et al. 2006). The difference among treatment groups is secondary to the speed of recovery and economic impact seen in groups assigned to Physical Therapy. Physical Therapy groups undergo a rapid improvement in the short term while the wait and see group takes up to 26 weeks to reach the same level of improvement. This rapid improvement in symptoms leads to decreased costs due to decreased utilization of health care resources in the coming year. The key question in the literature is what treatment should patients be provided with once they enter Physical Therapy.

Manual therapy including spinal and extremity joint mobilization and manipulation has been shown to reduce pain processing and improve pain and function. Pain free grip strength has immediately increased in response to these elbow interventions. These techniques are designed to reduce pain and allow a faster transition to an exercise program.

Exercise is one of the most important components of a treatment programs. Upper quarter exercises have been shown to reduce time off work and future medical costs, as well as, improve work and ADL tolerance (Pienimaki et al. 1998). Programs should gradually load the wrist extensors to restore coordination and strength to the tendon. A more irritable patient will benefit from isometric exercise whereas a more chronic, less irritable condition will benefit from eccentric exercises. Progression of the exercises should involve multi joint and functional movements to restore function in the upper quarter.

A recent review article suggests sub grouping patients based on their presenting signs and symptoms to best determine how to allocate these PT interventions (Coombes et al. 2015). These authors suggest advice, NSAIDs, and a wait and see approach for patients without risk factors for long term disabiilty, low pain severity and disability. Conversely, moderate and high risk patients with risk factors for long term disability, high pain and disability scores are most appropriate for pain medication and physical therapy interventions.

In conclusion, lateral elbow pain is not a homogenous condition and should be examined and treated based on an individual’s presentation for optimal outcomes.